Bio-City

Credits

Project:

Mikhail Kudryashov,

Simon Rasorguev

Collaborators:

Natalia Stepanova,

Irina Melnikova

Support:

Architectural Faculty of Yaroslavl State Technical University

Client:

The Modern Art Centre

“Ars-Forum”

http://x-4.narod.ru/bio

|

|

l`ARCA #183 | july-august 2003 | ISSN 0394-2147

Agora

Dreams and Visions

The concept

of a “network” spontaneously identifies with the idea of a “city”, if

for no other reason because of the way they evoke a smoothly knit system

of relations and functions underpinning both these notions. Needless to

say this identification goes way back into the past, starting with the

old city-state, the isolated, walled-in and self-sufficient polis capable

of radiating out a network of subordinated power relations or, at least,

powers of dissuasion, and reaching the modern city, openly integrated

in an endless array of connections feeding its intricate circulation of

information and decisions. In the postmodern era this situation evolved

even further, at least to the extent to which mobility and increasingly

refined means of communication have not just wiped out distances, they

have also eliminated the old network of locations and hierarchical scale

between small and large towns and cities. In the end, the cityscape has

turned into a mental place or cultural reference: no longer a clearly

defined spot on landscape but a momentary being-here-and-now marking an

order which is more temporal than spatial.

In a simulation like this, first defined back in the late 20th century,

the new and ever-spreading reality of computer technology and telematics

has emerged, altering the profundity or the urban design of modern-day

cities, not to the extent of undermining their historical premises but

certainly enough to mark a radical turning-point in how they are conceived.

The “web” is the urban reality of the age in which we live: a bodiless

reality finally wiping out space and time and giving rise to a different

line of thought based on simultaneity and immediacy. “The web is the urban

site now facing us”, so William J. Mitchell wrote in his La citta dei

bits (City of bits – Milan, 1998). But this is a brand new site that needs

totally rethinking. “This kind of city will be totally uprooted from any

definite point on earth”, so Mitchell goes on to say, “shaped by constraints

on connectivity and band width rather than accessibility and the positions

of properties, largely out-of-synch in how it operates, inhabited by bodiless,

fragmented subjects existing as collections of aliases and electronic

agents. Its places will be constructed virtually by software programmes

and not physically out of stone and wood; these places will be connected

by logical bonds instead of doors, corridors and roads. “But this forces

us to ask a crucial question that the future of architectural design will

have to focus its resources on: how will this kind of city be organized

and what will its socio-cultural fate actually be? Or, to quote Mitchell

again: “What kind of forum will we give the city of bits? Who will be

our Hippodamus?”

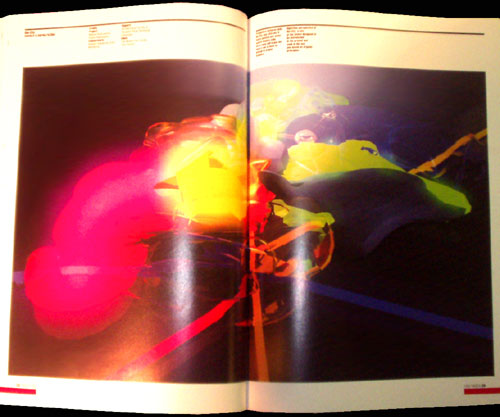

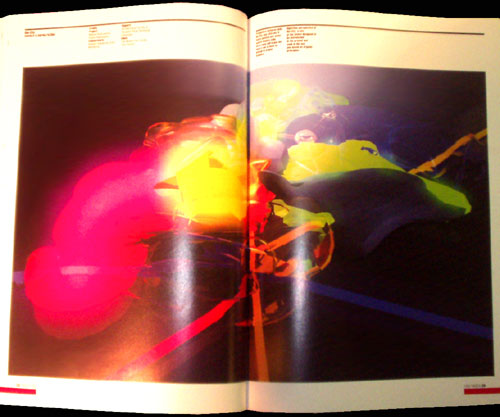

A possible answer to this question comes from Russia in the form of the

“Bio-City” project designed by Michail Kudryashov and his assistants.

Kudryashov has not just come up with a technological city, whose concept

of a web is merely a means to an implicit end, he has actually aimed at

designing a city that beats to the same rhythms as living organism capable

of adapting to various situations by altering its own structures, growing

or shrinking according to the community’s needs. The “network” here takes

on organic form. The comparison with a living body is more than just a

similarity: it is a model closely embodying the old utopian dream of a

city shaped around the functional/hierarchical structure of the human

body. Electronic devices, computer logic and the potential of telematics

here act like simple devices, whose worth does not depend on their efficiency

but rather the role they play in the entire system. The technological

optimism that is now so widespread, seeing technology as providing a solution

to all our problems and ignoring the constitutive absence of meaning this

explicitly denounces, is replaced by utopian optimism, still basically

unresolved, setting a simple scenario solely guaranteed by that deeper

meaning from the ethical component intrinsic to utopian planning. Talking

about his Bio-City, Kudryashov tells us that “the city turns into a pulsating

heart a slow beat.” Bio-City adjusts to the flow of presences in different

place and at different times of day, actually changing colour to represent

different functional states of affairs. “The various areas of the city

differ in terms of function, and the behavior of the bio-dome looming

above them changes with changes in situation. Even the appearance of the

bio-layer covering it depends on the population’s behaviour: e.g. it turns

red in case of danger… This means we are faced with a Chameleon-city or

Organism-city that safeguards and protects its population. In a word:

A Reasoning City.”

As we can see, Kudryashov`s Bio-City seems to appeal more to feelings

and emotions than to reason. Nobody expects utopia to analyse its own

feasibility and consistency, and it is obvious that the important thing

about this project is its ethical ends, its social drive expressed in

terms of deep psychology. A city that turns into the body and life blood

of its inhabitants and lives their states of mind contains within it a

certain mystical element in relation to which not just technological instrumentalism

but also planning and programming become sterile exercises in conceptualism.

Technological utopia and organic utopia lie at both ends of a scale on

which they are the most far-fetched projections. What we can do already

is to re-think the city, a fertile melting-port of technology and feelings,

starting with its architecture, so as to insist on rediscovering its authentic

humanization.

This is a difficult but not impossible task. A master of the 20th century

– and also the 21st to tell the truth – like John Johansen – has worked

hard on prospects like this, even envisaging architecture designed and

built according to principles governing the growth of human DNA. He has

even designed (l`Arca 179, March 2003) a “Growing House” based on the

idea of molecular engineering. Artificial DNA provides the basic material,

kept in a liquid state as the “seed” for instructing molecules that will

self-replicate in large quantities. “So-called “morphability” or the transforming

of a substance or elements into a certain form, position or quality, “so

Johansen writes, “will be one of the features of all MNT (Molecular Nano

Technology) products in the future. (…) Substances can be programmed to

be soft, flexible, rigid or hard, in order to let furniture meet the occupant’s

needs to change position.”

In this case the technology is constructive and not computerized, but

provides the essential reference point for a carefully designed utopia,

which, most significantly, is based on real possibilities, although at

the moment still only possible in the laboratory. This is what we might

call a utopia of meditation in which anthropologic inspiration feeds on

technical feasibility and scientific tests, which are reasonably reliable

for research capable of counterbalancing the visionary dream of setting

created for human happiness.

What really counts about this vision of the future is actually the key

role the city and architecture still play in relation to socio-cultural

progress of the society in which we live. Despite the diversity of the

sometimes rather radical ideas put forward, they all share the common

denominator of a “network” as a hub of relations and exchanges on a par,

which ever since ancient times, have always been at the heart of urban

agglomerates. It is no coincidence that history teaches us that all renewal,

desire for progress and, if you like, every revolution have always taken

cities as places of information, confrontation and mass communication,

the driving force behind them. But the space of a city is the space in

which its architecture is located, shaping both individual and communal

behavior, tracing its developments and adapting to them through constant

change. This means urban design concludes, as was the case with the masters

of modern architecture, with social planning; and, in this light, the

biosphere and bitsphere can come together to create a truly living, human

and creative environment.

Maurizio Vitta

|

|